Microplastics have now been found even in human bones — but what impact do they have on our health? Research is only beginning to uncover the scale of the problem, and the latest data suggests that these microscopic plastic particles can reach nearly every organ in the body, including the brain and bones, the BBC reports.

As early as the 19th century, a long-term agricultural experiment began in a field in Hertfordshire, UK, which today provides a unique opportunity to trace the consequences of human activity on the environment. For nearly two centuries, scientists have preserved samples of soil and crops, revealing everything from radioactive fallout after nuclear testing to early traces of microplastics.

Microplastics — small particles up to 5mm in size — enter the human body through food, water, and air. They have been detected in blood, saliva, lung fluid, breast milk, and even in the brain and bones. A 2024 study shows that microplastic intake has increased sixfold since 1990, especially in regions such as the USA, China, the Middle East, and Northern Europe.

The scientific community is seeking answers through so-called "human challenge experiments." In early 2025, eight volunteers in London will deliberately ingest a solution containing microplastics, simulating everyday scenarios such as drinking tea from plastic bags or heating food in plastic containers. Researchers will measure plastic levels in their blood over ten hours to determine how much is absorbed through the intestines and enters the bloodstream.

According to Dr. Stephanie Wright of Imperial College London, who is leading the study, it is likely that the smallest particles are the ones that penetrate the bloodstream. However, there is still insufficient data on how even minimal amounts of plastic affect a healthy person. The major question remains — where in the body do they accumulate, and does this lead to chronic inflammation or tissue and organ damage?

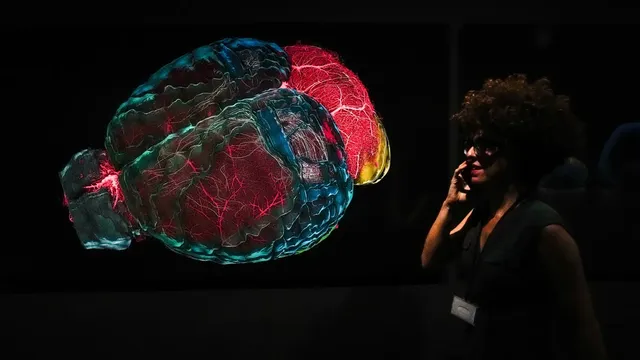

In 2024, Chinese scientists found microplastics in the bones and muscles of patients undergoing joint surgery. An Italian study discovered microplastics in the carotid arteries — the major vessels supplying blood to the brain. Patients with such particles were found to have a 4.5 times higher risk of stroke, heart attack, or sudden death within the next three years. In 2025, a new study detected microplastics in the brains of deceased individuals, with dementia patients showing up to ten times more plastic in their brains compared to those without the disease.

Scientists speculate that these particles may attach to fats, which the brain uses for energy, allowing them to enter the central nervous system. Moreover, the blood-brain barrier is weakened in dementia, making it easier for plastics to penetrate.

Despite the alarming findings, experts like Prof. Matthew Campen from the University of New Mexico emphasize that this is not about a direct cause-effect relationship but rather a long-term burden on the body. According to them, plastic particles act in concert with other harmful factors, worsening overall health.

Prof. Fay Couceiro from the University of Portsmouth says microplastics are not like asbestos — they do not cause a direct, acute disease but place additional strain on cells and the immune system.

The problem is compounded by the vast diversity of microplastics. A single liter of bottled water can contain up to 240,000 particles of various types. Some plastics absorb toxins or heavy metals, while others release hormone-disrupting chemicals. The smallest — so-called nanoplastics — are particularly dangerous, as they can penetrate cells and even damage DNA.

Microplastics can also act as carriers of antibiotic resistance genes. Prof. Couceiro’s project in Antarctica analyzes wastewater from cruise ships to identify plastics carrying such genes.

Prof. Raffaele Marfella from the University of Campania "Luigi Vanvitelli" believes microplastics can accelerate aging by damaging blood vessels, causing chronic inflammation, and disrupting cellular function. He uses lab-grown “vascular organoids” — 3D structures made from human cells — to determine toxicity thresholds.

Research shows that chronic exposure to microplastics may reduce the effectiveness of treatments in patients with cancer or chronic diseases. The particles bind with medications, altering their behavior and lowering their efficacy.

Prof. Couceiro and her team are also studying whether people with asthma and COPD are particularly vulnerable. They collect sputum samples and measure air quality in patients’ homes to identify inhaled plastic particles and assess their impact on lung cells.

In the long term, researchers hope to convince manufacturers to transition to safer plastics. For instance, hospital masks and tubes are often made from plastic — but is there a safer alternative that reduces risk for patients?

“We know microplastics are everywhere, even in our bedrooms. And even while we sleep, we’re inhaling them. It’s time to start thinking about how to reduce them at the very beginning of the chain,” says Prof. Couceiro. | BGNES

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria