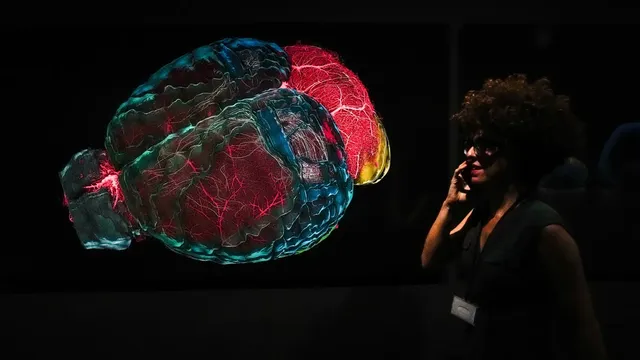

Alzheimer's, cancer, kidney failure. An international team of researchers is looking for commonalities in these age-related diseases. They may have found a way to disable it.

Who hasn't wanted to postpone death? A team of scientists is exploring this question and has even made a surprising discovery about aging, reports the journal Nature Oncogene, which takes an in-depth look at kidney disease - affecting nearly half of people over 75.

In her study, Karina Kern - the study's lead author, a former geneticist at University College London and director of biotech company LinkGevity - along with a group of kidney disease specialists, explored necrosis and how it could lead to new therapies.

The researchers believe that a new type of drug called an 'antinecrotic' could offer new treatment options for certain patients. But that's not all. According to the journal Popular Mechanics, this could be the first drug officially approved to fight aging in general.

The good and bad death of cells

Experts distinguish between two main types of cell death and stress that not all forms of cell death are harmful. Apoptosis is programmed and regulated cell death that plays a protective role - preventing the development of disease and cancer when it proceeds properly. Necrosis, on the other hand, is an unregulated process in which the cell dies in a chaotic manner, leading to uncontrolled tissue destruction.

Necrosis is the basis of aging

It is necrosis that underlies many age-related diseases - such as Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, cancer and kidney disease. In it, the affected cell swells to bursting, releasing its contents into the environment, causing inflammation, genetic instability and rapidly growing tumors.

The potential of antinecrotic drugs

Antenecrotic drugs could help people live with fewer diseases, especially in old age - at least that's what scientists working on the project hope. Scientists have known about the process of cell necrosis for more than a century, but it was only in the 1970s, with advances in microscopy, that they began to understand why it is so destructive.

At the heart of necrosis is the loss of calcium ion gradients, explains Karina Kern. Calcium levels inside the cell are typically 10,000 to 100,000 times lower than those outside. Calcium is a key signalling molecule that controls many cellular processes. Under stress, this regulation is lost, leading to the activation of multiple destructive intracellular pathways.

At the heart of necrosis is the loss of calcium ion gradients, explains Karina Kern. Calcium levels inside the cell are typically 10,000 to 100,000 times lower than those outside. Calcium is a key signalling molecule that controls many cellular processes. Under stress, this regulation is lost, leading to the activation of multiple destructive intracellular pathways. | BGNES

Breaking news

Breaking news

Europe

Europe

Bulgaria

Bulgaria